Two elements each of these seminal horror movies since 1960 have in common, Part II: Identity.

Two elements each of these seminal horror movies since 1960 have in common, Part II: Identity.

"I think of horror films as art, as films of confrontation. Films that make you confront aspects of your own life that are difficult to face." - Wes Craven

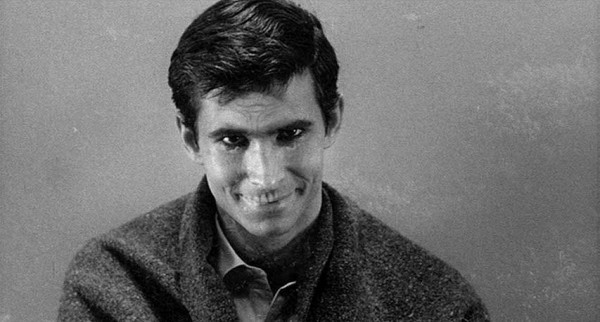

Norman has a little bit of his mother in him.

Part one of this article can be found here.

As far back as 1908's first known film adaptation of Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (no longer in existence) and 1919's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, horror movies have found the psychological explorations of "identity" to be effective proving grounds for stories that unsettle the mind. It is, after all, the major component of the self; whether attributed to a character in a story in terms of perspective, ideologies, beliefs and experiences, or the individual watching the film whose own experiences, perspectives and beliefs may be preyed upon by the storyteller manipulating their greatest fears.

The marriage of the two (character and observer) through the main character's perspective can enhance the emotional impact by placing viewers in the shoe's of another - something that many will attest to be one of the important virtues of storytelling: to safely experience predicaments of others without being directly exposed to them. Why? As Lisa Cron explains in Wired for Story: The Writer's Guide to Using Brain Science to Hook Your Readers from the Very First Sentence

Story, as it turns out, was crucial to our evolution—more so than opposable thumbs. Opposable thumbs let us hang on; story told us what to hang on to. Story is what enabled us to imagine what might happen in the future, and so prepare for it— a feat no other species can lay claim to, opposable thumbs or not. Story is what makes us human, not just metaphorically but literally. Recent breakthroughs in neuroscience reveal that our brain is hardwired to respond to story; the pleasure we derive from a tale well told is nature’s way of seducing us into paying attention to it.

Whereas the best of Science Fiction explores what makes us human, the best of Horror asks what are we capable of doing and demonstrates how far we will go - whether it's protecting through repression or the total annihilation to the complete loss of control amongst other things - when the self comes under attack. That we may not be who we think we are, or as others perceive us to be, as well as being capable of horrors that evoke cognitive dissonance may very well be the most frightening things about the dark side of human nature that the ten films discussed in the previous article exemplify.

"We all go a little mad sometimes..."

Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho is, at its essence, a modern take on the premise of dissociative identity disorder explored in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, both exploring multiple, distinct identities inhabiting a single body. Norman Bates, having killed his mother years ago, maintains the family's livelihood, The Bates Motel, while his mother's corpse stares oppressively with its blank eyes and wig...overlooking Norman from the house on the hill.

After the story disposes of whom we thought to be the main character - Marion Crane - we're locked in with Norman's perspective, seeing the world through his eyes. As discussed in Machiavellianism and The Usual Suspects, Hitchcock employs numerous techniques to keep the illusion that mother is indeed alive until the revelation at the film's climax. Once revealed, we find ourselves reassessing everything that came beforehand and see it in an entirely new context as to how far Norman Bates has gone to conceal his crime(s) not only from the public - but himself as well.

Note: Fans of Psycho looking for a surreal take on similar themes might find Alejandro Jodorowsky's Santa Sangre a very worthwhile watch having been named to Roger Ebert's Top Ten films (#6 1990) as well as his Great Movies list.

George Romero's Night of the Living Dead explores identity in a manner that's similar to Invasion of the Body Snatchers: the people who we think we know, love and trust aren't what they appear to be - shells of their former selves - but takes it a step further in that rather than clones, they're reanimated corpses of the dearly departed. As such, they're void of characteristics and personalities that made them recognizable aside from their physical attributes. They are us, but they're not - and as a metaphor for death, they're coming to get us... all of us, sooner or later.

"They're coming to get you, Barbara..." Johnny teased, only to end up becoming one of them.

In order to survive, we find the characters disassociating themselves from the departed - something that, at least in psychological terms, harkens back to warfare of the era and the dehumanization of the enemy by various means. Here the dead become an army of "things" or "ghouls," that, much like the enemies in war, must be destroyed. Failure to see them as anything but a threat jeopardizes the living such as with Barbara when she's faced with her brother Johnny's "return," hesitating just long enough - calling him by his name in hopes of some semblance of recognition - only to meet her own demise.

Much like The Walking Dead does on AMC, the film asks how far are we willing to go in an effort to hold onto our sense of self, a bit of an irony since at its basic level our existence and survival is predicated on de-evolution and "losing ourselves" to a certain extent (in the case of Barbara succumbing to Johnny - psychologically it would require an act of fratricide for her to survive, but physically the Johnny she knew and loved is already dead.)

Rosemary's Baby has a very different approach to the horrors of identity, yet echoes both The Exorcist and The Omen - not so much for their reliance on religious overtones, but from that perspective of the parent. Identity here is a culmination of various parts of the equation discussed before: thoughts, attitudes and beliefs lead to behaviors which, in turn, induce action (or reactions) which ultimately define characters.

For Rosemary, being pregnant with a child that may be used as part of a sacrifice is one thing... but being a mother, regardless to whom, is another. By the time she has her child and learns of its true fate, there's no turning back. Despite its identity as a child of Satan and her initial disgust, Rosemary herself - her identity - has changed to that of one becoming a mother, a role she seems to readily and willingly accept in the film's final shot.

In The Omen, much of the horror from the parental aspect results from the mystery surrounding the Thorns' adopted child, his origins and his subsequent identity as the antichrist after a series of disturbing deaths. The chain of events point to a carefully orchestrated scheme suggestive of Machiavellianism: Robert was chosen because of his own identity, that of an American Diplomat, allowing Damian to acquire political influence later in life.

Robert cannot, however, come to grips with killing his child at first, adopted or not. When he finally does commit to the act, his beliefs change by the culmination of events leading to the murder of his wife and revelation that their own natural child was killed at birth and his behavior seen as irrational by those who lack his subjective experience and knowledge. As a result, they believe he's acting erratic and wrongly in attempting to kill his child. His own identity - his persona - at this point perceived as broken for the lack of a better word, Robert is shot and killed just as he raises the dagger to stab Damian.

The Exorcist gives us every parent's worst nightmare: discovering their young daughter has turned into something other than sugar and spice taken to the extreme with a dash of heated possession and subsequent loss of control over oneself. While Chris MacNeil watches helplessly as her daughter succumbs to a series of unexplainable maladies, what the story is really about (as explained here) is faith - specifically the faith lost and subsequently regained by the story's main character, Father Damien Karras.

It is with Father Karras that audience experiences the story's thematic message through as a priest who's lost faith after the death of his ill and elderly mother... a priest who no longer believes in God. As mentioned earlier, beliefs play a crucial role in a person's attitude, behaviors and ultimately the actions they take - so much so as we can draw parallels between Karras's character and that of Regan's: both suffer an identity crisis in their own way, Regan's being physical versus Karras's spiritual.

His attempts to find a traditional explanation for Regan's malady failing, Karras eventually comes to believe she's in need of an exorcism - the first step in his rediscovering faith: if demons do exist, then so must God. But Karras is no exorcist, hence the need for Father Merrin. In the end, with Merrin having succumbed to Pazuzu, Karras finds the only way to save Regan is to fully regain his faith, exemplified by "God damn you!," and self-sacrifice, relinquishing his own identity and commanding the demon, "Take me! Take me!"

Carrie, like The Exorcist to some degree, also explores the changing of identity within a young girl. Rather than focusing on possession, the story deals with a sexual awakening during a teen's formative years made supernatural with the powers of telekinesis. All Carrie wants to be is normal - at least within the context provided by life outside her home as defined by her classmates.

Home, as Carrie knows it, is wherein much of their perspective of her comes from as a misfit raised by a religiously oppressive mother. The awakening Carrie goes through clashes with her mother's beliefs so much so the events, minus the supernatural context, are atypical of teenagers breaking away from their parental ties in an attempt to form their own identities.

Going on dates with boys and to the prom, these are things teenage girls identify with and things Carrie very much wants for herself. Not only does she believe they will make her normal in other people's eyes, she believes they will make her feel normal as well. When this sense of purpose to define oneself is confronted, we see how far Carrie will go in using her abilities to keep her mother at bay. But alas, much like Mrs. Bates, mothers seem to know best and Carrie falls victim to the cruelest of cruel pranks, resulting in her proving to be anything but normal.

Stanley Kubrick's adaptation of Stephen King's The Shining doesn't deal with identity in an overt manner. Rather, it uses narrative blurring to keep the audience on edge. Making numerous changes from the novel, the film is a bit more open-ended and somewhat suggestive - much of the horror seemingly coming from within Jack as opposed to a supernatural force. As a result, Jack is a less sympathetic character who appears to be suffering a breakdown from cabin fever vs. being a victim and subsequent tool of external forces.

Nevertheless, there are certain characteristics of the plot such as Danny's friend "Tony" who lives in his mouth whom Danny later uses self-referentially. There's also the case of the previous caretaker who developed cabin fever and killed his family which parallels the present with Jack, the Overlook Hotel July 4th 1921 ball and the the fact that "All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy" that lead to identity, or loss of it, playing a significant factor in the film.

The Shining's final image throws a little curve into the narrative.

The last three films, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Halloween and Scream deal with antagonists that, on the surface, wear masks to conceal their identities. On a psychological level, the purpose runs much, much deeper.

Leatherface, the most notable antagonist in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, proves the old saying to be true: you are what you eat. As a cannibal, he sews the skin of his victims together to create a mask - presumably to hide his own grotesque self, "the monster within," so to speak. But upon closer examination, the late film critic and author Robin Wood points out the question of identity extends beyond the family of cannibals

...but in their midst is Franklyn, who is as grotesque, and almost as psychotic, as his nemesis Leatherface. (The film's refusal to sentimentalize the fact that he is crippled may remind one of the blind beggars of Bunuel.) Franklyn associates himself with the slaughterers by imitating the actions of Leatherface's brother the hitchhiker: wondering whether he, too, could slice open his own hand, and toying with the idea of actually doing so. (Kirk remarks, "You're as crazy as he is".) Insofar as the other young people are characterized, it is in terms of a pervasive petty malice. Just before Kirk enters the house to meet his death, he teases Pam by dropping into her hand a human tooth he has found on the doorstep; later, Jerry torments Franklin to the verge of hysteria by playing on his fears that the hitchhiker will pursue and kill him. Franklyn resents being neglected by the others. Sally resents being burdened with him on her vacation. The monstrous cruelties of the slaughterhouse family have their more pallid reflection within "normality."

In the end, Sally's ability to survive is predicated on breaking out physically while suffering a psychotic break mentally, one that rivals her captors as she's pushed to the extreme and reduced to a state of fractured mind as much as they are. Indeed, just as with Psycho, Carrie, Night of the Living Dead and so many other seminal horror films, when we hold a mirror up to the monster it's often ourselves we see reflecting back.

Give this man a mask and a chainsaw and he wouldn't be all that unlike Leatherface.

As mentioned in the previous article, Robin Wood also questions whether Michael Myers in John Carpenter's Halloween is a victim of Dr. Loomis's constant projection of evil over the last nine years. Through Loomis's eyes, Michael is evil incarnate - a force of pure malevolence who wears a mask on Halloween. That the mask itself is pale white and void of emotion robs the character of an identity - the constant, neutral expression adding to the scare factor - while hiding his true self underneath. In this regard, the mask makes Michael anonymous: he could very well be anyone underneath and it's only near the end that we see the adult version lift it ever so briefly to expose nothing that resembles the possession of Regan in The Exorcist, but rather a normal looking person.

Fans of the movie who have read the screenplay know that Michael was referred to as "The Shape" in the script. In what appears to be a deliberate attempt to strip Michael of any humanity in the reader's eyes, The Shape becomes an omnipresent force - particularly on the screen when he's heard breathing rather than seen. While the mask initially gives Michael a sense of anonymity, it quickly - at least in the minds of Laurie Strode and the audience - becomes synonymous with "the bogeyman." In this sense, the film seems to form an argument as to whether the bogeyman actually exists - the final shots confirming that yes, indeed he does: Michael has evolved from a young boy committing fratricide early in the film to becoming a full-blown, walking incarnation of a myth.

Michael Myers aka The Shape aka The Bogeyman; from sister-killer to becoming a persona for a mythology.

Last, but not least, is Wes Craven's Scream - Kevin Williamson's ode to slashers of his youth. Half parody - half tribute, the film takes tropes in what arguably began with Carpenter's Halloween in the 1970's (itself somewhat stylistically reminiscent of Bob Clark's Black Christmas from several years prior) which had become cliched by the late 1980's/early 1990's and makes them fresh again.

With regards to identity, the killers forge their persona straight from how-to-make-a-successful-slasher. In other words, the killers' identity is an amalgamation of characteristics influenced from other movies, yet retains its own persona as an entity who knows a little too much about the history of the horror film. If Billy and Stuart weren't psychopaths by merely killing people, they surely were by the means they took to cover their crimes.

The teens in Scream themselves are weened on horror movies, so much so that their awareness aids in the film's self-referential style (self-referential here being to the genre it identifies with). As such, they're aware of the cliches and rules of your typical slasher setting - but also allowed to toss film references left and right, or as with Randy, actually live and breathe horror to the extent it's what, as a character, he identifies most with (as well as what makes him a credible, albeit expected, suspect.)

Ultimately it's Scream as a movie and its identification with its genre's expectations and cliches, both acknowledging and poking fun at them, that enables the film to stand on its own merits. Its post-modern "stab" at the growing debate involving the effects of media violence on "the self," something which had been brewing as a topic of interest after a generation or so exposed to more and more violence, also helps to elevate it to something more purposeful than your typical horror film.

With that last point in mind, we're brought somewhat full circle: As Robin Wood noted, horror in the 1930's was foreign. By the 1960's it began invading the fabric of our society with the disintegration of the family - something very much reflected in cinema the following decade plus as we watched it enter the home, both literally with the advent of technology (Cable, VHS and DVD) and figuratively with the stories playing out on the screen.

Whether or not there's any direct impact from one onto the other is an argument for another place and another time. That said, it is pertinent to note that it's no coincidence the exploration of identity is so prevalent in these films featuring the disintegration of the family; the family is where we derive our sense of identity from. From cultural norms to genetics to our upbringing, we're a product of many factors and influences - none stronger than family and what happens in the home.

Perhaps that's what Wes Craven meant with horror films make you confront aspects of your own life that are difficult to face.

Written By: James P. Barker

Film Reel Designed by Starline / Freepik